Fair and Square: The Planning Legacy of World's Fairs

By: Brendan Nee Written November, 2004

Introduction:

What started as a large trade show developed in to a forum for idea exchange which helped define architectural styles, planning movements and the way the world views technology. World's Fairs brought people together from around the globe for a year of festivities and exhibits which helped to shape society and promote the ideals of capitalism, free trade, competition, and the exchange of ideas. At the same time these fairs shaped their host cities by carving out space for future parks, providing transportation improvements, and leaving a few lasting civic buildings and monuments. World's Fairs represent a significant planning movement.

Origins:

The predecessors of World's Fairs were smaller scale trade exhibitions that occurred on a national level. One of the earliest of these was the Exposition publique des produits de l'industrie Francaise, which was held in 1798 in Paris in the Champ de Mars. The purpose of this fair was primarily political, the Republican government wanted to win approval and support from the entrepreneurial class through sponsoring the event. The goal was to stimulate a new "economic mentality" implying a switch to capitalism and innovation from the age-old guild system. The event lasted only a few days, during which products were displayed randomly with no categorization or sorting. (van Wesemael 846) More Parisian exhibitions followed at intervals of several years with improvements at each one including judging of products, sorting by industry, and lengthening of the duration of the event, allowing visitors from a wider area to access the fair. Other features of these early fairs include entertainment to draw the general public so that they might be educated while at the fair. This feature would be included in all subsequent World's Fairs. The buildings and exhibitions of these early fairs were demolished as soon as the fair was over so very little physical evidence of their existence remains.

The first exhibition of international scale was the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. It took place in Hyde Park and a huge Crystal Palace which was constructed specifically for the fair. It was the largest building of this type to be built, and was constructed right over the trees of the park. (Allwood 192) While previous exhibitions had attracted thousands of visitors, the Great Exhibition attracted millions, overburdening the transportation systems of London and resulting new transport lines being installed directly to the exhibition. (van Wesemael 846) This exhibition was promoted internationally and drew exhibits and visitors from Europe and the US. Displays included samples, prototypes, and scale models from various technologies as well as exotic goods from around the world. Foreign reporters used the telegraph wires strung across the continent to keep the Great Exhibition in international headlines. Also, the building itself was a marvel and helped draw an unprecedented number of visitors during the 140 days of the exhibition. This first international scale exhibition proved to be an overwhelming financial success with the profits were used to fund educational developments in art and technology. Because of its success, it was used as a model for all future exhibitions and World's Fairs, including New York and Dublin (1853) and Munich (1854). (Mattie 260)

Development:

As World's Fairs developed from trade exhibitions to international public relations tools, the profit motive became less important. Nations and cities provided financial backing for huge projects with the sole goal of topping previous exhibitions. These were seen as investments in promoting the city or asserting the importance of a particular host country. Each fair had to boast being bigger or more spectacular than the last in order to attract visitors. Notable World's Fairs after 1851 were the Centennial Fair in 1876 in Philadelphia and the Paris fair of 1889. The Philadelphia fair caught Europeans by surprise when they saw the quality of many American goods and exhibits. The fair featured the largest glass and iron exhibition hall yet constructed. The Paris Exhibition of 1889 featured the Eiffel Tower, and Parisian landmark which was at first fiercely opposed but later embraced as the symbol of Paris. The area around the Eiffel Tower was created into a park which was used for several more World's Fairs in future years.(Mattie 260)

The Columbian Exhibition:

The Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago was no exception to this. Chicago was struggling to assert itself to older east coast cities while the US was in the same position with Europe. By far surpassing all previous exhibitions in size and attendance, the Columbian exhibition, though delayed a year for preparation, established Chicago and the United States as the economic and cultural equals of the East coast cities and Europe respectively.

The exhibition was given 686 acres along Lake Michigan which was marshland, which was more than double the area devoted to any prior World's Fair. It used three times the amount of electricity normally required by the city of Chicago and emphasized new themes such as transportation and energy.(Bolotin 166) The fair was organized around a long pool named the court of honor, and buildings were designed by the top Chicago architects, under the supervision and coordination of chief of construction Daniel Burnham. There was a consistent architectural design between the buildings on the court of honor, including classical style, uniform cornice height and color. This contrasted to previous fairs which were held either in one enormous building, or in several unrelated and uncoordinated buildings. (Allwood 192)The only exception to this consistency was the transportation building designed by Louis Sullivan which differed in all aspects from the rest of the fair.(Burg 381) He believed that the architecture of the fair should be more varied and modern, not relying on ancient classical styles. Sullivan may have accurately predicted that "the damage wrought by the World's Fair will last for half a century from this date—if not longer" because the legacy of "City Beautiful" planning would live on long beyond the fair. (Hilton 191)

The final outcome resulted in all buildings being painted white, and though they appeared dignified and permanent, they were all made of plaster and designed to be demolished at the end of the fair. In fact, the fair was financed partially though pre-selling the building materials of each structure as scraps. Many of the massive trusses for the buildings were designed to be divided up and sold as individual railway train houses once the fair was over. (Bolotin 166) The rest of the fair's funding came from five million dollars in bonds from the city of Chicago, five million dollars in private funds from Chicago's business elite and boosters, and projected fair attendance revenue.

The impacts of the World's Columbian Exhibition extend very far. First of all, the fair impressed foreign visitors and helped established the US as a world power. The fair was grander and better organized than any held previously in Europe and the displays of American technology were impressive compared to the European technologies. It prompted many new inquiries and subsequent sales for US exhibitors from foreign firms. Most exhibitors easily recovered the costs of their exhibits. (Allwood 192)

The fair also established Chicago as a dominant US city, no longer content to be called "Porkopolis". (Burg 381) The fair inspired Chicago to create a center for the arts in Rome and the Field Museum of Natural History. Also, it inspired groups across the Midwest and the country to establish "Arts societies" in communities which previously paid little attention to the arts. This embracing of the arts helped to make Chicago a more cultured and cosmopolitan city.

Finally, the fair established a renewed interest in city planning in the United States. Visitors were so impressed with the grandeur and style of the white city that they returned to their hometowns and rallied for a similar development at home. The white city is reported to have inspired Catherine Lee Bates to write America the Beautiful, L. Frank Baum to dream up the Emerald City, and Walt Disney to devise theme parks, specifically Epcot Center in Orlando, FL through tales of the white city passed from his father who was a carpenter at the fair. (Bolotin 166) (Hilton 191) Also, one of the most influential architects of the twentieth century, Frank Lloyd Wright, was working as an apprentice of Louis Sullivan, designer of the dissenting Transportation Building and no doubt was influenced by Sullivan's thoughts on Architecture and the fact that his building was the only one to win an architectural award offered by a European agency. (Bolotin 166)

The white city was Daniel Burnham's earliest expression of "City Beautiful" design and was a precursor to his 1907 plan for Chicago which specified the same type of civic deign. This movement sparked plans for beautiful civic spaces in downtown areas in the Beaux-Arts style, with a uniform and consistent plan in most major US cities. While these plans were only implemented in a handful of cities, the influence of the fair extends to hundreds of "Roman temples and baths, Florentine villas, and French palaces and gothic Churches and universities, to say nothing of office buildings which retained ill-chosen souvenirs from all these crumbled civilizations".(Badger 177) Certainly the fair was not entirely responsible for the "City Beautiful" movement or the emergences of public buildings across the country in historical styles. However, it was certainly an important milestone in the development of this movement.

Further Development:

Notable World's Fairs after the 1893 Columbian Exhibition included Paris (1900 and 1925), St Louis (1904), San Francisco (1915 and 1939), Barcelona (1929) and Chicago (1933). The 1900 Paris Fair promoted the Beaux-Arts style which became so popular after the Chicago fair in 1893. Also, the second Olympic games were held at the fair in Paris, though they were a measurable failure due to lack of support. (Mattie 260) Four years later at the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition of 1904 in St Louis (then the fourth largest city in the US), the third Olympic Games were held with little fanfare. While the games failed to attract much attention or participation, the Fair was a huge success and built off of the popularity of the Beaux-Arts planned "White City" with its own "Ivory City". (Birk 96)

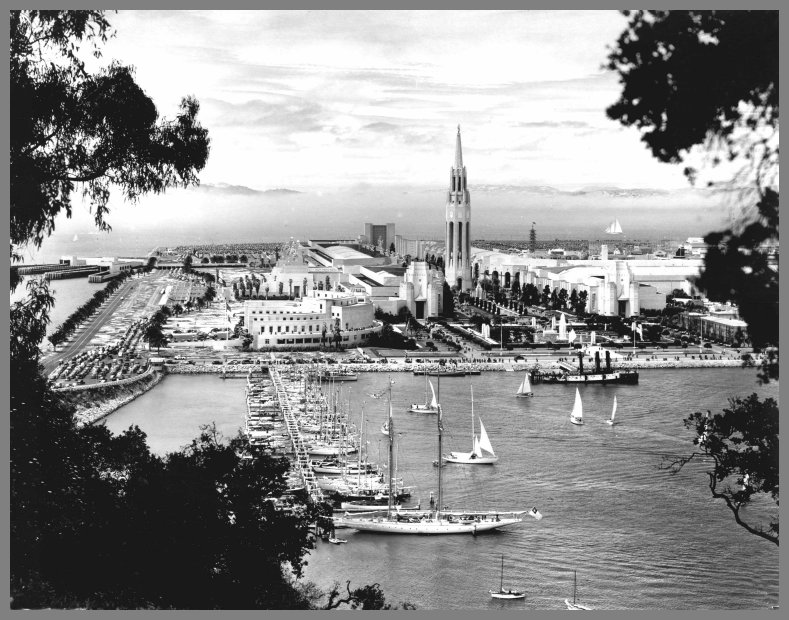

San Francisco exhibited the its vision of the "Jewel City" in 1915, which was more colorful, but still Beaux-Arts, than the previous "White City" or "Ivory City". Later in 1916, San Diego popularized the Mission Style of architecture with its Panama-California Exhibition. (Fox 129)

Architecture was again at the forefront of the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris. This World's Fair helped popularize and validate the streamlined and playful Art Deco style. Le Corbusier exhibited his "Machine for living in" while extolling his five points of architecture. It was here where he unveiled his "Plan voisin" which called for leveling most of Paris and replacing it with parks and towers. This modernist plan was not popular, but foreshadowed urban renewal schemes that would take place decades later in the US.(Mattie 260)

Chicago's 1933 fair was planned by Beaux-Arts trained architects but executed with stripped down modernist buildings and was the first World's Fair to focus its theme on celebrating progress. This led the way to the largest and most futuristic fair ever held.

The New York World's Fair of 1939:

The 1930s saw an array of fairs promoting progress in both Europe and the US. New York sponsored a fair of a size that dwarfed all previous fairs, covering 1,126 acres in what used to be a swamp, in Flushing, Queens. Previous fairs were no larger than half the size of the New York fair, and it was also one of the costliest fairs ever produced.(Zim 240)This was an area that Robert Moses, as City Parks Commissioner had always wanted to develop as a park, and as usual he got his way.( DAWN OF A NEW DAY: THE NEW YORK WORLD'S FAIR, 1939[123])

This fair ended a decade which started with a stock market crash, and so it was natural that the fair look to the future for a theme: "Building the World of Tomorrow with the Tools of Today." A very futuristic style of architecture including streamlines art Moderne, and International Style Modernism was present and imposed over an underlying Beaux-Arts style layout. However, without the classical architecture and uniform design guidelines like were imposed in 1893, the fair's vistas were fragmented. Streamlines, clean shapes, and new materials characterized the buildings of the fair. (Mattie 260)

Many new and influential technologies were displayed and popularized at the New York fair, including advances in radio, communications, television, color photography, labor saving electrical devices, home building materials, and most importantly, transportation.(Zim 240) Exhibits on the newly emerging mode of air travel were popular, and the rail and ship industry had sleek buildings and exhibits. However, the exhibit that stole the show was the "Futurama" exhibit, sponsored by General Motors. This exhibit gave visitors an aerial ride through a landscape dominated by a revolutionary superhighway that seamlessly connected urban and rural areas. Notably, the initial panorama did not include any gas stations or car sales sites, nor any churches or schools. Maps of the US showing all cities connected by freeways hung near the entrance, and exhibits of the increasing speeds of travel over time showed that superhighways were the next step in transportation progress. ( DAWN OF A NEW DAY: THE NEW YORK WORLD'S FAIR, 1939[123])

During the ride, visitors saw freeways that clung to the sides of vast canyons, soared over cities with futuristic buildings and saw prototypes of interchanges that allowed all vehicles to maneuver at 50 miles per hour. (Gelernter 418)The end of the ride brought the visitors to the "present" where they could view a wide array of GM vehicles currently for sale. Other major auto manufacturers were present at the fair and had equally futuristic exhibits. Ford built a looping test highway for visitors to test-drive its cars on. Chrysler and Goodrich teamed up present an automotive racing and stunts show which showed the durability of their products (and the excitement that cars can bring).(Zim 240) Twenty-seven million people waited up to two hours to see the Futurama exhibit throughout the duration of the fare, and it no doubt helped to influence the public perception of a publicly funded superhighway system and a society of automobile ownership. (Rydell 269)

The New York World's Fair was laid out differently than past fairs. The pavilions for nations were given relatively unimportant and obscure locations while major American companies' exhibits dominated the prime spots. Also, there were many entrances, one for each mode. The Long Island Railroad had a special stop, each of the three subway companies had a stop and there was an entrance near a parking lot for people who drove. This was one of the first World's Fairs to have large amounts of people arriving by automobile, and this was accommodated by Robert Moses' widened parkways. ( World Fairs: New York; San Francisco[282]) Robert Moses would preside over the next New York World's Fair in 1964 as President of the World's Fair Corporation and his influence could be felt throughout the fair. (Bletter and Queens Museum 208)

Influences on Planning:

World's Fairs had huge influences on society and specifically on planning. World's Fairs introduced the latest technology to the general public. The Columbian exhibition popularized the use of electricity, especially for outdoor architectural embellishment. (Bolotin 166) Future exhibitions promoted energy, communications, and mechanical innovations that influenced and changed society in powerful ways which in turn influenced planning.

Transportation was first given serious exhibition space at the Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, 1893. If focused primarily on innovations in railroads and locomotives. Nine years later, the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition in St Louis (1904) showcased private automobiles or "horseless carriages" and offered many people their first glimpses or brief rides in these contraptions. This was a very popular attraction at the fair and no doubt helped to promote the idea of the automobile. (Birk 96) The 1939 New York World's Fair promoted the idea of freeways and the freedom brought though automobile use and the GM Futurama exhibit was the most popular exhibit at the fair. Also at this World's Fair, new building technologies enabling cheaper and better single family homes were on display. A community of detached single family homes was built on the fairgrounds and dubbed "The town of Tomorrow". (Bletter and Queens Museum 208) This emphasis on the car and single family home being part of the future, and the overwhelming popularity of these exhibits were influential in the way transportation and cities were planned.

World's Fairs also had more direct influences on their host cities. Many cities now have a massive park in a central area of the city which once hosted a World's fair. In some cases this area was originally a park and was significantly improved for the fair, in other cases it was carved from wilderness or otherwise unused land. San Francisco built an island in the Bay for its Golden Gate International Exhibition of 1939 and 1940 and became an airport and then a naval base. (Reinhardt 169) In these various parks, a few fair buildings or monuments often remain. St Louis has an Art Museum and bird cage in Forrest Park from 1904, Chicago saved the Museum of Science and Industry and Alder Planetarium. (Hilton 191) Paris has the Eiffel Tower, Seattle the Space Needle, and San Diego has an array of museums in Balboa Park in buildings that once housed the World's Fair. In some cases, popular buildings were relocated or rebuilt after the fair. The famous Crystal Palace of the London's Great Exhibition of 1851 was rebuilt in Sydenham, south of London and pleased visitors until it burned in 1936. (Mattie 260) The Palace of Fine Arts from the San Francisco Panama Pacific International exhibition was saved, and then completely rebuilt in the 1960s after serving as military jeep garage during the war. (Allwood 192) World's fairs have left a legacy of civic structures and park improvements that last well after the completion of the fair.

World's Fairs strained cities in many ways, but most substantially in the area of transportation. Fairs were used as justification to build needed improvements to the transportation system or to spawn new systems. Starting with London in 1851 which built additional transit lines to the fair as a result of overwhelming demand, fair planners have focused on transportation issues. The Columbian Exhibition in Chicago provided the impetus to extend the "L" to the fairgrounds.

Some fairs celebrated transportation achievements. The Panama Pacific Fair in San Francisco in 1915 celebrated the completion of the Panama Canal, later the San Francisco Fair of 1939 celebrated the completion of the Bay and Golden Gate bridges. Robert Moses widened freeways leading to the Flushing fairgrounds in New York in 1939, Seattle built a monorail for its fair in 1962, (Allwood 192) and Montreal built its Metro for the Exposition of 1967. These transportation improvements had been planned prior to the World's fairs, but the fair provided the reason to construct them. Even modern fairs have caused cities to reevaluate their entire transportation plans, such as Knoxville (1982) and New Orleans (1984). (Urban Systems Associates 1 v. (various pagings))

A final influence of World's Fairs has been planning and design. These exhibitions allowed for experimentation in planning and architecture in ways that would likely not have been allowed or funded outside the context of the World's Fair. Top architects and planners were commissioned for each fair, as the host city and country wanted to impress visitors. The Chicago Columbian Exhibition in 1893 kicked off the city beautiful movement across the country, while the New York fair of 1939 exposed visitors to international style architecture which had impressed visitors to Mies Van der Rohe's German Pavilion in Barcelona a decade earlier. ( DAWN OF A NEW DAY: THE NEW YORK WORLD'S FAIR, 1939[123])

Most importantly, World's Fairs helped to legitimate planning as a profession. Massive fake cities more beautiful than any real city were built very rapidly under the supervision of planners and architects, and then disappeared even faster. World's Fairs required a tremendous amount of organization and planning and the results were spectacular. They made the public aware of planning issues and inspired interest in planning in cities across the US.

Legacy:

World's Fairs provided a venue to showcase ideas and cultures. Most World's Fairs focused on new technology that promised progress. From ingenious labor saving devices imported to the 1851 London Great Exhibition from the former colonies, to the Futurama of 1939, a view of a utopian and auto based future, people came to the fair for a peak into the upcoming technologies that would shape their lives.

Also, World's Fairs are founded on the ideas of free trade and intellectual exchange. The planners of the original 1851 London Great Exhibition had the goal of tapping into new markets for British products in mind when organizing the event. (van Wesemael 846) Countries and firms scramble to show off their best innovations at World's Fairs to attract buyers and also to gain ideas from competitors.

World's Fairs are a stage for competition. Competitions between companies over who can make the best products occurred in this open market setting. Another element was the competition between cities and countries over who could host the largest, most impressive fair, topping all previous attempts.

Finally, World's Fairs were based on capitalism. The products on display were either for sale or prototypes of ones that would soon be available. It was assumed that buying available new technologies would fuel the development of an even broader range of new products. World's Fairs started out as oversized trade shows and a large portion of most World's Fairs were given over to marketing and promotion of various products.

Evolution:

After World War II, World's Fairs continued to be popular but none topped the size of the 1939 New York World's Fair. Seattle (1962), New York (1964) and Montreal (1967) were all successful fairs. They were all based on futuristic themes. Seattle built the fair on land condemned by the city, and topped it with the Space Needle. (Mattie 260) The 1964 New York Fare was used by Robert Moses to generate funds to restore the park that was left vacant after the 1939 World's Fare in his honor. In the end, the fair ended up being a financial disaster but the park did end up being fully developed and many of the features of the 1964 fair exist to this day. (Bletter and Queens Museum 208) Montreal's World's Fair was themed "Man and his World" and it incorporated humanist themes. It left the city with an island park well served by transit. (Hilton 191)

Since 1967 the impact of World's Fairs has been diminished. Nations and cities are more reluctant to sponsor such events, as costs soar and budgets tighten. Construction requirements have become more intensive and costly while fairs do not draw the level of attendance they used to. Scarce land in many cities and the potential environmental impacts block fairs from happening as well. Also, modern visitors are less impressed with the spectacle that World's Fairs provide and it becomes more and more difficult to top the previous years fair. Modern communication, transportation, and entertainment technologies have made the World's Fairs that first promoted these technologies somewhat obsolete. Still, fairs can be useful for the original reason they were started; for promotion of trade.

Lessons:

World's Fairs played an important role in exposing the public to new technologies, cultures, and ideas. They provided a stage for experimentation in architecture and planning and place to promote the latest styles. The technologies presented at World's Fairs changed the way people lived, and had huge impacts on planning.

While World's Fairs do not have the influence they once had, other international events, such as the Olympics are more popular than ever. While the Olympic Games are a shorter duration event, thanks to advancements in communication, they are broadcast around the world, along with images of the Olympic venues and the host city. Thus, many elements of World's Fair planning can be translated to Olympic planning. The Olympic Games leave the host city with parks, sports venues and supporting buildings which outlive the games for decades. With the number of people watching the Olympics increasing with every game, venues have become increasingly costly and well designed.

Beijing is sparing no expense in constructing some spectacular venues for the 2008 Olympic Games in the order to promote China as a fully developed country. The bid for the 2012 Olympics is featuring the same cities that originally vied for the right to host the earliest World's Fairs with Paris, London, and New York submitting bids along with Madrid and Moscow. These bids include significant planning developments including significant developments along prime real estate in New York. Thus, major world events are still relevant but the time frame has been collapsed from a year long fair to a few weeks of sporting events.

An important lesson to learn from World's fairs is that they live on through the parks, buildings and public spaces that they once inhabited. These spaces should be designed with the after-event uses in mind. While the plaster buildings or past World's Fairs were removed shortly after the fair, the transportation enhancements, street patterns, and park locations are relatively permanent features of most World's Fair host cities.

Conclusions:

World's Fairs have helped to shape cities and entire planning movements. Many technological developments related to planning have been spurred at World's Fairs. They have encouraged automobile use, spawned new transit systems, urban parks, museums, and monuments that became icons of cities. They provided a test bed for planning and architectural theories and ideas. World's Fairs brought people together from around the world to promote the ideals of capitalism, free trade, competition, and the exchange of ideas. At the same time as people were educated, they were entertained and enlightened with art and culture. Though the era of huge World's Fairs is over, the legacy of World's fairs lives on though huge international scale events such as the Olympic Games.

Works Cited

Allwood, John. The Great Exhibitions. London: Cassell & Collier Macmillan, 1977.

Badger, Reid. "The Great American Fair : The World's Columbian Exposition & American Culture." .

Birk, Dorothy Daniels. The World Came to St. Louis : A Visit to the 1904 world's Fair. St. Louis: Bethany Press, 1979.

Bletter, Rosemarie Haag, and Queens Museum, eds. Remembering the Future : The New York world's Fair from 1939-1964. New York: Rizzoli, 1989.

Bolotin, Norm. The World's Columbian Exposition : The Chicago World's Fair of 1893. Ed. Christine Laing. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

Burg, David F. " Chicago's White City of 1893." .

DAWN OF A NEW DAY: THE NEW YORK WORLD'S FAIR, 1939. NEW YORK, NEW YORK: QUEENS MUSEUM, 1980.

Fox, Austin M. Symbol and show : The Pan-American Exposition of 1901. Ed. Lawrence D. McIntyre. Buffalo, N.Y.: Meyer Enterprises, 1987.

Gelernter, David Hillel. 1939, the Lost World of the Fair. New York: Free Press, 1995.

Hilton, Suzanne. Here Today and Gone Tomorrow : The Story of World's Fairs and Expositions. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1978.

Mattie, Erik. World's Fairs. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998.

Reinhardt, Richard. Treasure Island; San Francisco's Exposition Years. Ed. Scrimshaw Press. bkp. San Francisco: Scrimshaw Press, 1973.

Rydell, Robert W. World of Fairs : The Century-of-Progress Expositions. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Urban Systems Associates. 1984 Louisiana World Exposition Statewide Access Plan. Ed. Ozarks Regional Commission and Louisiana. Office of Aviation and Public Transportation. New Orleans, La.: The Associates, 1982.

van Wesemael, Pieter. Architecture of Instruction and Delight : A Socio-Historical Analysis of World Exhibitions as a Didactic Phenomenon (1798-1851-1970). Rotterdam: Uitgeverij 010, 2001.

World Fairs: New York; San Francisco. New York: Time, inc., 1939.

Zim, Larry. The World of Tomorrow : The 1939 New York World's Fair. Ed. Mel Lerner and Herbert Rolfes. 1st ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.