Analysis of the Berkeley Class Pass

By: Brendan Nee and Courtney Pash

Written Dec 3, 2004

Introduction

Transit offers numerous benefits to individuals, communities, the environment and employers. Like most commodities, the price can be substantially lower if bought in bulk or as a group. Deep discount group pass programs offer neighborhoods, employers, campuses and other groups the ability to provide their members discounted transit while promoting the use of transit and reducing the amount of parking required. Berkeley has a successful Class Pass program for its students and has recently started a similar program, the Bear Pass, for employees. However, these types of pass agreements require tedious negations regarding funding, equity, and implementation issues. Numerous studies have shown that deep discount group pass programs across the United State have been successful in substantially increasing transit ridership and guaranteeing a continuous revenue stream to the transit agency. However, it remains to be seen whether the Berkeley Bear Pass can overcome the negotiation and implementation hurdles to become widely accepted and considered a success.

Definition of Deep Discount Group Passes

Deep discount group passes offer a large group of people transit passes at deeply discounted rates. Typically all members of a specified group are eligible to receive transit. The group collectively pays for the transit passes on behalf of the eligible individuals. The funding for these passes can come from direct user fees charged to all participants, other types of user fees such as parking revenues, or from the group′s general funds. The funding can be a controversial part of the development of a deep discount group pass (Miller, 2001).

Deep discount group pass programs work in a similar way to an insurance policy. Not all members of the group will use the pass, and so this helps to cover the cost of those who use transit frequently. Transit agencies end up with increased revenue that is generally greater than the additional costs incurred from the additional ridership and administrative costs from the deep discount group passes (Nuworsoo, 2004).

Types of Deep Discount Group Passes

There are three types of programs. One type is opt-in, where members of the group must sign up or decide to pay the fee up front. This type of program usually encourages the lowest level of participation since it requires all members to take an action to become involved in the program. Thus, group members who are not interested in participating will not join and also some who are interested may decide not to take the action of opting-in. A second type of program is opt-out. In this program, all members are automatically enrolled unless they take a specific action to be removed from the program. An opt-out generally encourages more participation than an opt-in program because many people who are unsure if they want to be enrolled will decide to stay in and avoid the steps necessary to opt-out. The last type is a mandatory program. This can be administered by not directly charging individuals the transit fees and instead having the group cover the cost, as is the case in some fully employer sponsored programs, or it can be done by simply charging a non-optional fee to all members, which is common in campus based deep discount group pass programs. This non-optional fee is typically much lower than a regular unlimited transit pass and also significantly lower priced than if an out-in system were in place, hence the name deep discount.

Brown, Hess and Shoup demonstrated that opt-in programs have the highest cost per participant and the lowest participation levels while opt out programs do significantly better and mandatory programs provide the lowest costs and an obvious 100% participation level. This is because mandatory programs eliminate the effects of adverse selection which is the tendency for individuals who frequently use transit anyway to be the only opt-in program participants, thus the cost of providing the required service to these riders is relatively high. This necessitates higher charges for universities and students, which discourages occasional riders from participating. Also, when not all students are covered, the benefits of knowing that everyone has a transit pass for group travel or class field trips are eliminated (Brown, Baldwin, & Shoup, 2001).

Benefits

College campuses are the most common places to find deep discount group passes. Campuses are generally high density destinations and college students often do not own cars and are more likely to use transit to begin with. A study of 35 campus based deep discount group pass programs in 2001 by Brown, Hess and Shoup listed benefits for both universities and transit agencies that offer deep discount group passes. The benefits to universities and students included reduced demand for parking, increased access for students, and a better image for the university (for recruitment purposes), as well as the usual benefits of increased transit use such as lowering costs of transportation (when compared to driving). Also, it has been shown that these types of transit passes can reduce employee absenteeism and increase morale among employees (Meyer, 1996). It makes an attractive perk to help recruit new employees and allows universities to attract employees who rely on transit as their only mode of transportation.

The same study cited benefits to transit agencies as being increased ridership, a guaranteed revenue source, and improved transit service overall (Meyer, 1996). Increased ridership effectively lowers the cost per passenger and subsidy per passenger and can sometimes allow a transit agency to expand service. Deep discount group passes increase total transit ridership and improve transit service while decreasing cost per rider, subsidy per rider and total operating subsidies (Brown et al., 2001).

Ridership Increases

When transit usage increases as a result of implementation of deep discount group pass programs, communities receive the typical benefits of reduced traffic congestion and improved air quality. Also, the entire community benefits when deep discount group pass programs necessitate expansions of transit service and improvements such as schedule and route information at shelters. In general, increased ridership results in a stronger transit system that can provide better service to its customers. While regular transit riders may experience more crowding on certain routes because of deep discount group pass programs, the increase in transit service and efficiency in boarding due to the prepaid nature of the program offsets this disadvantage.

Finally, deep discount group passes for university students can cause students who have not used transit before to become familiar with and experience it. Because it is free, many students will try using transit for their commutes or errands. This experience with transit may cause students to continue to use transit and consider it when making a residential location decision later in life, even if they move out of the area. This early experience with modes other than single occupancy vehicles may stay with the students for the rest of their lives. Thus, the deep discount group pass for students is a method of educating younger people about transit and building ridership for the future.

Experiences at Other Universities

One of the earliest examples of deep discount group passes is the Pioneer Valley (Springfield-Amherst Area) Transit Authority and their UMASS transit program. This service started in the 1960s and connects the city of Amherst, MA with five colleges: UMass-Amherst, Hampshire, Amherst College, Smith and Mount Holyoke. It is free for everyone, including residents, students, and faculty/staff. Funding for UMass transit comes from the local, state and federal governments as well as from each of the five universities it serves (Doxsey & Spear, 1981).

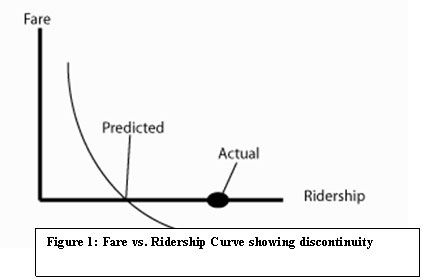

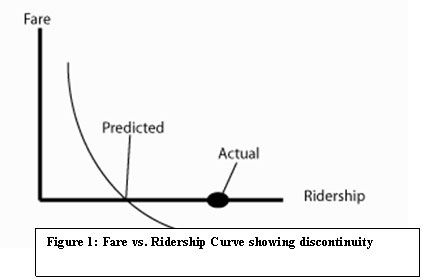

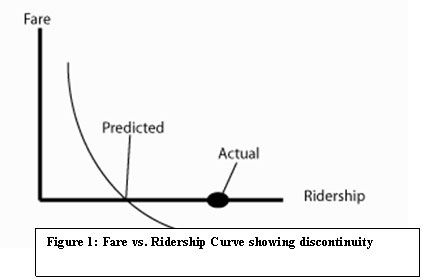

When deep discount group pass programs are implemented, huge increases in transit ridership are recorded. The primary reason for increased ridership is the reduced fare. The Simpson-Curtin rule estimates fare elasticity to be -0.33. This would imply that when fares are set to zero (decreased by 100%), the increase in ridership would be 33%. However, Hodge has estimated that actual ridership increases by roughly 50 percent, with a discontinuity in the demand curve as shown in Figure 1 (Hodge, Orrell, & Strauss, 1994). This discontinuity occurs when fares are effectively set to zero, which is the case with a deep discount group pass. This can be attributed to the increased utility of transit when the psychological barrier of the fare box is removed. The uncertainties of transit fare pricing and the need to carry exact change intimidate some people, but these uncertainties are removed when a pass program is implemented. Also, for some people, paying a fare every time a trip is needed is less desirable than using a car, where a large amount of money is a sunk cost and users do not need to worry about paying per trip.

Beyond reduced fares, Brown, Hess, and Shoup identified improved service, rider education, residential relocation, reduced automobile ownership, and the benefits of traveling together (Brown et al., 2001). As ridership increases and a guaranteed revenue stream for the transit agency is secured, transit service tends to improve. Some agencies also increase service to campus areas in anticipation of increased ridership. Second, by giving all members of a group a discounted pass, they are more likely to learn about the various transit routes and the destinations they serve. Thus, people participating in a deep discount group pass program are more likely to try transit for trips they had previously believed could not be accomplished on transit.

After a deep discount group pass program has been in existence for a while, individuals may begin to make residential location decisions based on the availability of transit. Members of this group may look for better housing in neighborhoods where parking is scarce but transit service is good. Similarly, some members of the group may forego the expense of automobile ownership and rely on other modes because of the availability of the deep discount group pass.

Finally, ridership also increases because of the group factor. Under typical fare conditions, the larger the group, the more likely that group is to use an automobile for their trip. This is because the cost of making the trip in an automobile is fixed regardless of the number of people, up to the vehicle′s maximum. With standard fares, the group incurs no savings using transit because each additional person requires and additional fare. When only some members of a group have an unlimited transit pass as would be the case with an opt-in or opt-out deep discount group pass setup, the group may still choose to travel by car because not everyone has a transit pass. However, with a mandated deep-discount group transit program, it is free for all members of the group to use transit for their trips, which may inspire groups to use transit that would have otherwise driven. Additionally, it has been shown that the presence of a University wide transit pass has encouraged more field trips and off campus activities for classes (Meyer, 1996).

History of the Berkeley Class Pass

In April 1999 a student referendum was voted on with 30% voter turnout and 89% approval and the Class Pass began. This referendum called for a "tax" on every student of $10 per semester. This charge would provide students with a deep discount group pass, dubbed Class Pass, giving them unlimited access on AC Transit for each semester for the next three years. AC Transit, the City of Berkeley, the University and students had been working on accomplishing their transit related goals through a mutually beneficial transit program since the fall of 1990 (Levin, 2000).

The goal of any business endeavor is to maximize revenue and decrease costs and in transit agencies this holds true and includes minimizing rider subsidies, externalities, and unused capacity while providing the highest level of service possible. AC Transit also wanted to "strengthen its voter constituency" in order to maintain approval of revenue yielding ballot measures (Levin, ). As discussed above, deep discount group pass programs provide transit agencies with increases in transit ridership as well as guaranteed revenue enabling them to improve overall transit service (Brown et al., 2001).

At the same time, the City of Berkeley was attempting to decrease congestion around campus and its corresponding environmental problems. One goal of the Berkeley General Plan, Transportation Element is to "Reduce automobile use and vehicle miles traveled in Berkeley, and the related impacts, by providing and advocating for transportation alternatives and subsidies that facilitate voluntary decisions to drive less" (City of Berkeley, 2001). The University shared the city′s interest in mitigating the environmental impacts of the traffic generated near the University. Additionally, the University wanted to reduce the demand for parking. There are approximately 7 parking permits issued per University parking space causing most parking lots to be at capacity during school hours. While looking to reduce the demand for parking, the fact that on-campus parking is a source of revenue for the University likely played a part in the negotiation process.

Prior to the implementation of the Class Pass, Berkeley and AC Transit experimented with a number of alternatives, consisting primarily of opt-in student transit passes. In 1990 the first of these passes sold for $80 and 1,800 students purchased them. When the price increased to $145 in 1997 the number sold fell to only 600 (Levin, ). Over the next two years, the price was lowered to $60 and the University provided a $50,000 subsidy, during which time they were negotiating the deep discount group pass program. In 1998 all sides agreed on the unlimited access plan, making it mandatory for all students to pay an additional charge that would show up on their tuition statement. The student charges were assessed at $18 per semester: $10 ACTransit Fee, $1 for free access to the perimeter shuttle, $1 administrative fee, and $6 for the 1/3 mandatory return to financial aid program. Additionally, the University agreed to subsidize all transbay trips by $1 per trip. According to a usage study by ACTransit, prior to the start of the deep discount group pass program, this arrangement was predicted to result in an average fare per person of $.50, but actually ended up costing only $0.26 per ride. The agreement did not allow for any fee increases during the three-year trial period. Any increase would have to wait until the trial period was over in 2001. In the first online election at Berkeley, in November of 2001 the students overwhelming voted to continue this program at the new rate of $34.20 for the first two years and $37.20 for the last two years.

The anticipation of the increased ridership resulting from the Class Pass forced ACTransit to improve and expand its existing routes (Cole, 1999). Additional signage was placed at all bus stops around campus and route maps and schedules for the routes serving campus were distributed with the Class Passes.

History of the Berkeley Bear Pass

Beginning in 1999 a petition was circulated requesting action by the Berkeley Department of Parking and Transportation to provide better transportation alternatives for faculty and staff, including both parking and transit improvements. The Bear Pass was finally approved and implemented in October 2004 (UC Berkeley Parking and Transportation, 2004). It is available to Berkeley faculty and staff living within a designated service area for $20 per month (pre tax). This is a substantial discount from the regularly offered $100 per month pass (including transbay service). Another major difference is that the Bear Pass is an opt-in/opt-out program, much like the original and less successful Berkeley student pass from the early 1990s. The Bear Pass program is a pilot program scheduled for the next two years, and "the Parking & Transportation department is continuing to work with AC Transit to expand eligibility."( Class Pass Referendum, 2003).

According to Norah Foster, a UC staff representative, it was challenging to get the Bear Pass approved and in her opinion there are many aspects of the program that do not satisfy the needs of a large portion of the faculty and staff. Her understanding of the problem is that Berkeley′s Parking and Transportation department depends on the revenue generated from parking fees and parking tickets. "It′s very difficult for them to subsidize their own demise (the parking empire)." The Parking and Transportation department had profits of over 2.7 million in 2003 but these funds are earmarked only for expansion of parking. Norah was likely referring to the fact that the Bear Pass may only be purchased by employees who live within AC Transit′s area of operation, excluding San Francisco. Thus, employees who live in farther out suburbs or San Francisco cannot even get the Bear Pass. This is especially surprising since AC Transit serves the San Francisco transbay terminal frequently and is a feasible commuting option. Employees who are eligible (those living in the East Bay) are eligible to take transbay busses, however since they do not live in San Francisco this will not be a commuting option for them. Employees have also asked for a deep discount group pass valid on BART and AC Transit, both of which serve the Berkeley campus.

Some of the reasons for the difference in cost and eligibility between the Bear Pass and the Class Pass have to do with the different nature of the groups. While students, who have commuting schedules that often occur during off-peak times or in reverse directions, fill many of the empty seats that AC Transit runs during the day, employees generally have regular schedules that coincide with the peak period and will add substantial strain on the transit system. Thus, in negations AC Transit clearly wanted to make sure that the users who put the most strain on the system pay for the additional service required. Despite this strain, the Bear Pass falls in line with the goals of the University and the City of Berkeley to "establish partnerships with adjacent jurisdictions and agencies … to reduce parking demand and encourage alternative modes of transportation by promoting programs such as the AC Transit Class Pass for students and employees to reduce parking demand" (City of Berkeley, 2001).

Analysis of the Class Pass

A before and after survey of students regarding the Class Pass was performed and analyzed in a dissertation by Nuworsoo. The survey showed that before the Class Pass was implemented, 5.6% of students used AC Transit as their primary commuting mode to campus while it increased to 8.7% after one year and 14% after two. Also, the proportion of students using "Other transit" was found to have increased from 0.2% to 1.3% which likely reflects more people using BART because of the easy access to BART stations from campus on AC Transit. The study found no statistically significant shifts away from driving, walking, or BART, though the mode share for all of these did decline. This may show that while the Class Pass did effectively increase transit use by 250%, it did not have a significant effect in reducing congestion or parking demand. Even though transbay busses became free under the Class Pass program, the share of BART mode actually increased (Nuworsoo, 2004).

Survey results indicated after the class pass was implemented that 38% of students changed mode of travel between the first and second year of the class pass with 9.9% citing a change in residential location and 3.6% citing the Class Pass as the primary reason. Thus the Class Pass did play a significant role in changing the travel mode of students during the first year.

Other results from the survey showed that the overall average travel distance decreased by about 10% in the first year of the Class Pass. However, the rapidly changing real estate market in the bay area may account for much of this shift. The study examined students′ mode choice by distance that they lived from campus. It showed that most AC Transit users lived between 1 and 5 miles from campus while BART riders lived 5-40 miles from campus. This can be explained by the mode: buses are slower than BART and thus students living further than 5 miles from campus would have an arduous and lengthy commute if using AC Transit. This would cause them to shift to a faster mode or to move closer to campus. Travel times were compared from before and after and found that overall average travel times increased slightly, which may be caused by increasing traffic congestion and the generally longer times for transit trips (Nuworsoo, 2004).

The same study confirmed that students do not contribute very much to congestion on busses during peak hours. The majority of student travel occurred during the off-peak hours as many students depart for campus after the morning peak period and return before or after the evening peak period (Nuworsoo, 2004).

Finally, the impacts on AC Transit were analyzed based on before and after ridership and the level of fare revenue generated from the Class Pass. It was estimated that AC Transit received 50% more revenue from the Berkeley student market or $406,000 annually with the introduction of the Class Pass, while ridership jumped 260%. However, it was shown using conservative assumptions that this increase in riders would move AC Transit from its 27% of seats occupancy to around 70%, thus not exhausting existing seat capacity or requiring extreme expansion on the part of AC Transit. Of course, expansion of a few key routes by increasing the size or frequency of busses would be required (Nuworsoo, 2004).

The Bear Pass was recently developed but is part of a larger initiative by the city of Berkeley to develop an employer sponsored pass. The first step was to establish a deep discount group pass program for employees of the City of Berkeley. Dubbed ECO Pass, for "Employee Commute Options", the program began Jan 1, 2002 and is still in effect. The City of Berkeley ECO Pass is a mandatory program available to all city employees automatically and is entirely funded by the City of Berkeley.

A before and after survey found that the City of Berkeley ECO Pass increased ridership on AC Transit from 6.3% to 10.7% during its first year. While this is a 75% increase it is small in actual numbers and did not necessitate expansion of AC Transit service. Moreover, the ECO Pass was found to be used 26.2% of the time at midday implying that it was being used by people with flexible work schedules or for non-work travel, which did not contribute to crowding during the peak period. The ECO Pass yielded revenues of between $2.00 and $2.50 per boarding which is three times the system average. It was calculated that AC Transit received an annual increase in revenue of $50,880 from the city employee market (Nuworsoo, 2004). Thus, the ECO Pass provides a relevant and successful model for the Bear Pass at the University of California Berkeley.

The University of California is the largest employer in the city, so the Bear Pass was seen as a key step in establishing a program that both large and small employers could offer and one that could eventually be offered to different neighborhoods in the city much like has been done in Denver and Santa Clara. The Bear Pass differs from the ECO pass mainly in that it limits members of the group from participating based on the location of the residence, it is an opt-in program, and part of the cost charged directly to the employees. These three differences work against the effectiveness of the program which is seen as an essential step in establishing a framework for similar programs around Berkeley and the other areas served by AC Transit.

Outlooks for the Class Pass and Bear Pass

The analysis stated above, the overwhelming student approval in the 2001 referendum, and the extension of the program to faculty members, are just some of the more visible indicators that the deep discount group pass program is a success. MTC also credited the program for its success: "students who never used transit before are now regular riders. And AC Transit is adding buses and new routes around the campus to meet the increased demand. In short, transit has become a viable option for many students who in the past would have added to campus-area gridlock." Based on this positive response it is likely that the Class Pass will continue for at least another four years. The question remains as to how much students are willing to pay for the Class Pass. While the cost of the pass doubled when it was renewed in 2001, it is not likely that the pass price will increase as much in future years. The 1998 prices were set before the program had begun and thus were based on assumptions and projections. The new price, set in 2001 after the trial period, was adjusted to match on a per ride basis what other discounted riders were paying. Therefore, ACTransit is unlikely to demand a higher payment and any increase still needs to be approved by the students when the Class Pass comes up for a vote in 2006.

The future of the employee Bear Pass program is less certain. Because it was initiated just two months ago, its success is yet to be determined. Thus far (Nov 23, 2004) 430 people have signed up for the Bear Pass out of a total of 8,000 allotted passes for faculty and staff. The program requires 1,300 participants to break even. Without this level of participation, funds from other alternative transportation programs will be used to cover the shortfall. According to Nadeson Permaul, director of Berkeley Parking and Transportation "We have a significant pool of employees who live within a ten-minute walk of AC Transit stops and within five miles of the campus. We have two years to achieve this goal, but the annual costs recur each year (fees paid to AC Transit for the program and implementation costs). We hope that employees will join over the course of the year, but the sooner the better." Based on these statistics, it is questionable whether the Bear Pass will be as successful as Class Pass.

Some explanations for the low Bear Pass participation are the opt-in structure, the timing, lack of promotion, the costs, or the limited eligibility. As stated above, an opt-in structure like that of the Bear Pass encourages the lowest number of participants out of all the types of deep discount group pass programs. Opt-in requires action on the part of employees and many who may be willing to try the pass may not be willing to go through the effort of buying a pass. This was the case with student opt-in transit programs at Berkeley in the mid 1990s prior to the Class Pass. Also the slow start may be partially due to poor timing. The Bear Pass was initiated in the middle of a semester, and employees had likely already arranged transportation for the semester such as parking permits. Employees with parking contracts might wait until their contract expires on July 1 st to buy the pass. Also, employees who might consider changing residential locations or selling a car to take advantage of the pass have not had sufficient time to make these major changes.

Employee sentiment indicates that the program is a step in the right direction; however a few changes seem necessary if the program is going to succeed. The program should be expanded to allow all faculty and staff to be eligible regardless of where they live. The Bear Pass could also be offered on an opt-out or mandatory basis to greatly reduce the costs to each individual and encourage increased participation. Also, improved marketing efforts, lowered costs through subsidies, and raising the price of parking may help to boost participation. It is likely that more employees will sign up in future months, especially at the beginning of next semester.

Conclusion

The Berkeley Class Pass and Bear Pass are just small steps in a larger vision of implementing a city wide deep discount group pass available to all employers and neighborhoods. The Class Pass has been shown to be successful in promoting transit ridership, increasing revenue to transit agencies, and saving money for students during its six year life. The Bear Pass, while similar to the City of Berkeley ECO Pass, has some key differences which may affect its success, although it is too early to draw any conclusions. However, deep discount group passes have been shown to be successful in improving service, reducing costs, increasing revenue, building a ridership base, and encouraging mode shifts from driving to transit across the country when implemented correctly.

References

2001 Class Pass Referendum - Class Pass Back by Popular Demand(2003). . Retrieved 11/14/2004, from http://public-safety.berkeley.edu/ p&t/classpass/referendum.html

City of Berkeley General Plan: A Guide for Public Decision-Making(2001). . Retrieved 11/14/04, from http://www.ci.berkeley.ca.us/planning/landuse/plans/generalPlan/Intro.html

UC Berkeley Parking and Transportation: Bear Pass . Retrieved 10/25/04, from http://public-safety.berkeley.edu/p&t/transportation_alternatives/bear_pass/

Brown, J., Baldwin, D., & Shoup, D. (2001). Unlimited Access. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Cole, M. (1999). Class Pass Necessitates AC Transit Upgrades. Berkeley, CA:

Doxsey, L. B., & Spear, B. D. (1981). Free-Fare Transit: Some Empirical Findings

Hodge, D. C., Orrell, J. D., & Strauss, T. R. (1994). Free-Fare Policy: Costs, Impacts on Transit Service and Attainment of Transit System Goals Washington State Transportation Center .

Levin, J. Distributive Cost Pricing: An Effective Strategy Toward Building Transit Ridership Quickly among Targeted Markets. Oakland, CA: Alameda - Contra Costa Transit District.

Meyer, J. A. (1996). In Beimborn E., United States. Dept. of Transportation, Wisconsin. Dept. of Transportation, University of Wisconsin-- Milwaukee. Center for Urban Transportation Studies and Technology Sharing Program(Eds.), An evaluation of an innovative transit pass program, the UPASS : Final report. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Transportation : Distributed in cooperation with the Technology Sharing Program.

Miller, J. H. (2001). In Boswell P. L., United States. Federal Transit Administration, National Research Council . Transportation Research Board, Transit Development Corporation and Transit Cooperative Research Program(Eds.), Transportation on college and university campuses : A synthesis of transit practice. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Nuworsoo, C. K. (2004). Deep Discount Group Pass Programs as Instruments for Increasing Transit Revenue and Ridership. Berkeley, CA: University of California Berkeley.